The 2024 Tānko Institute Summer Session will be held July 11, 12, & 13 in San Marcos, Texas.

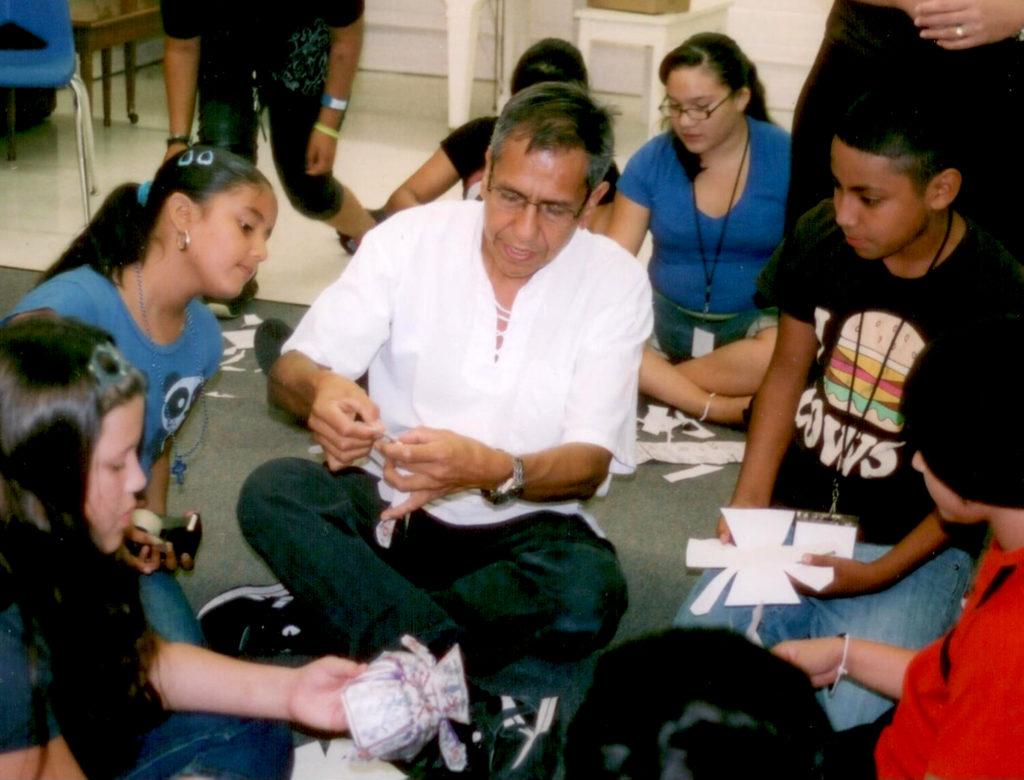

Indigenous Cultures Institute has designed a three-day training for school teachers and educators working with students K-12 outside classroom settings, to help them develop curriculum, lesson plans, and activities to teach in an Indigenous way using the Xinachtli pedagogy. This training offers ten hours of Continuing Professional Education credit.

After completing the training, teachers will be able to plan and execute eight specific activities for their classrooms, and build on that knowledge for additional lessons.

Participants will also be connected with a growing circle of trainees with whom they can exchange ideas around their implementation of the pedagogy in their practice.

The first training was launched on July 18 – 20, 2022 and successfully graduated fifteen participants. For more information contact the Xinachtli Training Coordinator, Marial Quezada at marial@indigenouscultures.org.

The word Xinachtli is a Nahuatl word describing the moment a seed germinates. There is nothing more powerful than a seed. A seed can crack a slab of concrete with its sprout. It can lay dormant for decades and awaken with its fruit. A seed is powered by the full intent of the Universe, designed by Creation to explode with Life.

One is the Sun

Two is the Earth

Three are the Animals

Four are the People

Five is the World

Six is the Sky

Seven is the Moon

Eight are the Birds

Nine are the Seasons

Ten is Death

Eleven are the Waters

Twelve is Community

Thirteen are the Stars

Zero is Infinity

Twenty is Complete

One is the Sun

Indigenous Pedagogy as an Adjunct in the Classroom

by Carlos Aceves

No culture can survive if it attempts to be exclusive.

– Mahatma Gandhi

When a social group feels it needs to impose on the resources of another group, its members do not simply tell themselves it is “time to act like thieves.” Rather they seek ways of justifying their actions. At that point, they might begin differentiating themselves as “civilized” while others are labeled “uncivilized.” For example, the official script is that the United States is in Iraq not to possess the country’s oil wealth but to “bring democracy” to an “undemocratic or backward” society. All cultures that become imperialistic begin creating an ideology that presents their culture as normal and civilized thus justifying their imperialism. Thus, they give themselves an “exclusive” right over those on whom they impose their power.

When I decided to draw upon my Mesoamerican heritage as a source to recreate a process of undoing whiteness in the classroom, I faced a dilemma. Was I recreating the colonial process described above by focusing exclusively on my own ancestral culture? I resolved this contradiction through focusing on process rather than content. I realized that the initial attempt of all groups is to create a means of survival for their culture and ensure the survival of coming generations by passing on this knowledge. The need for the “exclusivity” of that culture arises only when the original structure created by the group is transformed in an attempt to take and control the natural resources of other groups.

When I started attending Canutillo Elementary School in 1960, I encountered overt racism and a sociopolitical message that wreaked havoc with my self-esteem: to be Mexican was bad. Only through the Chicano Movement almost ten years later did I realize I was being conditioned to occupy a lesser position within the political and economic system of the United States, a society that had long ago become imperialist and colonialist.

Throughout my schooling the invasion by the United States of Mexican territory had been justified by portraying Mexico as an undemocratic country. Texas had been severed from Mexico because its new residents wanted “freedom.” Arguments in favor of the taking of the rest of Mexico simply followed the same reasoning. As my seventh grade history teacher told us, “The Mexican-American war was just as important to Mexicans as it was to Americans. Mexicans would finally have a free country to live in.”

However, my anti-imperialist consciousness which developed through the Chicano Movement helped me not to abandon the idea of using cultural awareness as a pedagogical tool in a similar way that we had used Mexican American culture as a weapon against white supremacy. Within the roots of any culture, there are the human aspirations for freedom, dignity, and artistic expression. As cultures become imperialist or subjected to imperialism, these aspirations become distorted and suppressed but find their way across history in the form of social struggle that often shakes the foundations of the contemporary society in which they now operate. The Xinachtli Project evolved under these circumstances and conditions.

Copyright 2023 – Indigenous Cultures Institute | Site by Xica Media